Boycott action began immediately, and spread rapidly. On 7 May production stopped at 13 different Coke bottling and canning plants in Norway. In Italy, several short stoppages occurred at Coca-Cola plants while workers met to hear reports on the situation in Guatemala. Austrian unions wrote to the local Coca-Cola management threatening action. In Mexico, ten different bottling plants held solidarity strikes for three days each on a rotating basis, while in Sweden all five IUF affiliates staged a full production and sales stoppage for three days.

News of further union action plans reached Atlanta: a week-long production, sales and distribution stoppage in Norway due to commence on 4 June; an indefinite stoppage to begin in Denmark on 15 June; and, probably most worrying of all, a national boycott campaign by a coalition of IUF affiliates and church and consumer groups scheduled to start in 16 US cities on 21 May. The Presidents of around 19 North American unions publicly announced that they would support the boycott.

The company was ready for a tactical retreat. Under pressure from the US unions, it agreed to a meeting in Costa Rica with representatives of STEGAC, the IUF and the Guatemalan Ministry of Labour. After two days of intense negotiation a settlement was signed on 27 May. Coca-Cola agreed to sell EGSA to a ‘reputable’ buyer and to prevent the two non-union Coca Cola plants in Guatemala from poaching EGSA’s sales territory; it guaranteed that the new owners would recognise STEGAC and the existing bargaining agreement; it also guaranteed to employ and pay the surviving 350 workers (96 had by now taken redundancy pay) until the plant re-opened; finally, the plant would re-open with all 350 employees and no-one would be laid off unless sales failed to reach an agreed target within 60 days.

While the agreement represented a considerable victory for STEGAC, it contained one concession to the company: the IUF was not a party to the agreement and therefore would no longer retain quite the same watchdog role it had had since 1980. But there was another, less obvious catch: no buyer had yet been found and Coke Atlanta refused to take over the plant in the meantime. Would the new owner accept and abide by the terms, and if not, would the US company assume responsibility? The IUF felt that it had got the best deal available even if its own formal role was no longer recognised: ‘The only real guarantee lies in the capacity of our affiliated unions and of our friends for quick mobilisation.’ In the light of the agreement, the boycott was called off.

Under the terms of the agreement, US$252,000 was allocated for back-pay for the workers (about US$240 per month each). They could also claim the Official re-opening of the Coke bottling plant, 1 March 1985 remainder of the redundancy fund set up by Zash and Méndez at the time of the closure which should suffice in lieu of wages until the plant re-opened. According to company calculations, there was enough to last until September.

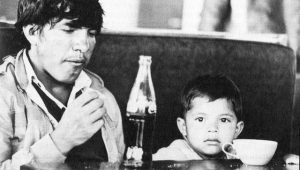

In the event, no new buyer appeared. When the IUF’s regional secretaries visited the plant in mid-August, they reported that although the morale of the workers had understandably fallen, a sense of calm prevailed. One major problem was medical expenses as there is no national free health service in Guatemala. Since national insurance payments were no longer being made by the company, the workers and their families had to pay for all medical care. The workers were still determined to see the occupation through to the end.

Settlement

As September wore on and still no buyer appeared, the IUF warned its affiliates to gear up once more for boycott action, and gave the company an ultimatum to come up with a solution by 10 October. Coke Atlanta now claimed to be negotiating with three potential buyers, and the federation reluctantly decided to allow more time, while keeping its affiliates on standby for a resumption of the boycott. By early November, with negotiations with buyers still in progress, STEGAC’s funds were completely exhausted, and the IUF once more appealed for contributions.

Finally, on 9 November Coca-Cola announced that it had signed a letter of intent to sell the plant to a consortium led by Carlos Porras González, a reputable economist who had run businesses in El Salvador. The first meetings between the union and the new prospective owner were not encouraging. Porras claimed to have no knowledge of the Costa Rica agreement of 27 May. He said that he had no obligation to former employees; that the union no longer existed since its members had collected their redundancy pay; and that he would hire fewer workers and at a lower wage. The IUF was outraged and demanded a new meeting with Coke Atlanta.

The company refused: the 27 May agreement had only been an ‘understanding’; the matter was now entirely for negotiation between the workers and the new owner; and the company was not willing to intervene, nor to hold further meetings with the IUF.

Porras was playing a double game: holding off against Coca-Cola to negotiate the cheapest terms and the least possible commitment to what he saw as hangovers from the previous regime at EGSA; and pushing the union to accept more redundancies. Meanwhile the market for Coca-Cola in much of the capital city was being supplied by the non-union plants in Retalhuleu and Puerto Barrios.

For STEGAC and the Coca-Cola workers the situation was very serious.

Christmas came and went, with still no settlement. Most had received no pay since September, and the funds sent by the IUF were only enough to coyer basic necessities. Only their discipline, their confidence in the IUF and the steady stream of messages of support from abroad sustained them.

Finally, on 1 February, just over two weeks short of the anniversary of the start of the occupation, an agreement was signed. Porras’ consortium would operate the plant under a new name, Embotelladora Central SA. EGSA had been declared bankrupt and the company dissolved. STEGAC, too, was formally dissolved, but a new union, STECSA, was formed from the membership of the old and recognition was guaranteed. Initially only 265 workers were re-employed, but if production and sales reached agreed levels, more would be hired with preference given to former employees.

The settlement was a good one, although it was less than the union had hoped for after the meeting in Costa Rica. All sides had made some concessions: the union had allowed some redundancies; Porras had given full recognition to the union and higher manning levels than he wanted; and Coca-Cola had assumed some of the financial responsibilities of the bankrupt EGSA.

Repair work began in February and work officially resumed on 1 March.

On 20 March, the first bottles came off the production line and two days later the plant was officially re-opened in the presence of the Guatemalan President, Mejía Victores and the US Labour Attaché. STECSA was recognised by the company and received legal registration on 11 April. Early production figures were good and 52 more workers were taken on. STECSA signed an agreement releasing Coca-Cola from its obligations under the agreement reached in Costa Rica the previous May, and received a further US$250,000 to cover back pay and compensation for those made redundant.

ln an advertisement inserted in Guatemalan newspapers STECSA gave its verdict on the victory:

We want to make clear to posterity that the decisive factor in winning this solution to our problems was the unity shown in the moral and material solidarity given to our union both from within our country and internationally by our brothers and· sisters in many countries. A vital role was played by the IUF.

Sisters and brothers, workers of different countries the world over, members of churches, fellow Guatemalan workers: this victory is yours, because your belief in the struggle for workers’ just demands has been vindicated.

The power of example

The occupation at EGSA had begun in the midst of renewed repression of trade unionists, which continued throughout the period of the dispute. In March 1984 the former general secretary of the Diana confectionery factory escaped kidnapping but with serious gunshot wounds, and sought asylum in the Belgian Embassy. Four more trade unionists were kidnapped in mid-May. ln January 1985 Carlos Carballo Cabrera, a leader of the trade union federation CUSG (1 CFfU affiliated) was kidnapped and tortured. A leader of the Ray-O-Vac battery workers union and two from the El Salto sugar mill were kidnapped and disappeared. Another worker from the CA VISA glass factory was kidnapped on 17 February 1985 and found dead on 13 March. He had been tortured. Why were the Coca-Cola workers not touched?

Undoubtedly their greatest defence was their international support from the IUF, from the ICCR shareholders and from Coke consumers all over the world. Coke Atlanta was probably telling the truth when it claimed to have urged the utmost restraint on the Guatemalan government: its own vital image and reputation were at stake, and the IUF had given ample evidence in April 1984 of its ability to generate a powerful and damaging campaign of publicity and boycott.

Although the Guatemalan military undoubtedly wanted to destroy the union, they recognised that this time the tactics had to be different. With elections promised and a pressing need for foreign aid, they could not afford to go back to being the pariahs of the international community. Like Coke Atlanta, they believed the union’s resolve would crumble as time passed.

Both the government and the corporation were wrong. The Coke workers’ struggle proved to be exception al in the labour history of Guatemala – and perhaps anywhere in the world – for the remarkable persistence with which a group of workers pursued the right to form a trade union for more than nine years. The key factor behind the success of the year-long occupation in 1984 was the extraordinary discipline of STEGAC’s members and its leadership. The morale of the occupation was sustained by the permanent presence of the STEGAC executive committee and the daily routine of maintenance, cleaning, guard duty, assemblies, and education and leisure activity. As a result, only a few workers accepted redundancy pay.

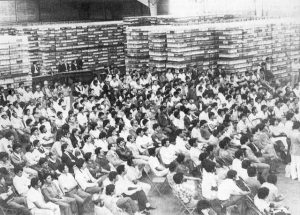

Finally, STEGAC was sustained throughout the occupation by the involvement and support of other Guatemalan unions. They recognised that if STEGAC was destroyed, their own tentative efforts to revive union activity would be greatly jeopardised. During the occupation, the EGSA plant became a safe meeting place and a nerve centre for other trade unions. As a member of the British Parliamentary delegation witnessed in October 1984:

At very short notice STEGAC organised a meeting for us at the plant of some 30 trade unionists representing ten different unions. The leaders wanted us to know what the general conditions of the Guatemalan workers were like. Two things impressed us about the meeting: first, the way the leaders did not take the floor, but let the rank-and-file speak for themselves; and second, the way the various members each explained how they had suffered from the repression. A wide cross section of trade unions including the municipal workers, university students and workers in sugar mills, textiles and glass, had all lost leaders. Their crime? All of them were involved in some kind of negotiation with management or were simply demanding the right to form a workers’ trade union.