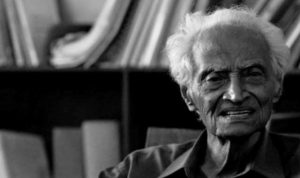

Bala Tampoe Memorial Meeting, London, May 23, 2015

Comrades, Friends,

I thank you for the invitation to this meeting to honour the memory of a comrade who meant so much to all of us.

Bala was active in the international trade union movement, at first in the international trade union federation where I was general secretary, the International Union of Food and Allied Workers, the IUF, later in several other Internationals, and I want to tell you something about his role.

First, how we first met. I had been a student in the United States and in the early fifties I had joined the youth organization of the Independent Socialist League, the split from the Fourth International which was headed by Max Shachtman, so I had become aware of the Trotskyist movement in Ceylon, the LSSP and the union movement associated with it.

In 1960 I started working for the IUF as an assistant to the general secretary, Juul Poulsen. The IUF had been up to then a largely European organization, and Poulsen and our Executive decided that we had to become truly international. After Latin America, Asia became our priority. I was the editor of our news bulletin which we started sending to all the unions we knew about that were potential affiliates, among which the CMU.

Bala later told me that was the bulletin that caught their attention. May Wickremasuriya, his wife who was at the time assistant general secretary of the CMU, told him: “look at that, these people are saying the same thing we are saying”. We started exchanging information.

In 1968 I was elected IUF general secretary, to the surprise of many and, to some extent, to my own surprise. I invited the CMU to affiliate and Bala invited me to meet him in Paris, at the secretariat of the Fourth, for a discussion.

I think he may have been testing me, but I had no problem with meeting him on the premises of the Fourth and we immediately got along. Following that meeting, the CMU decided to affiliate to the IUF, their first international affiliation ever. This was in the early 1970s.

The CMU became an important union in our Asia/Pacific Regional organization, and Bala was elected to the Regional Committee. It turned out that he would be playing a crucial role in defending our principles and defining our policy.

At the time we had another affiliate in Sri Lanka, the Ceylon Workers’ Congress, the CWC, led by Saviumamoorty Thondaman. This was the organization of the Tamil workers on the tea plantations in central Ceylon. The CWC was also affiliated to the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, the ICFTU, and Thondaman was influential in its Asian region.

We had a joke about Thondaman, we said he was in his person the embodiment of ILO tripartism. He was a deputy in the Sri Lanka parliament as well as a minister in several governments; he owned a small plantation, where he was an employer; and he was as well the leader of a trade union.

The ambiguity of his position led him to lose sight of trade union principles: in his government role, he supported the adoption of legislation restricting the right to strike. This was a breach of the IUF Rules. Bala raised the issue of which we might otherwise have been unaware.

Several months passed where the regional as well as the international secretariat argued and pleaded with Thondaman to stop supporting the anti-union legislation. Thondaman refused to change his position, so the IUF congress in 1981 had before it a resolution, endorsed by the Executive and the Regional Committee, to expel the CWC. The discussion was short, and the decision was unanimous.

Thondaman was the kind of trade union leader who believed himself to have a dispensation from normal rules of trade union behaviour and he was shocked by the decision of the IUF congress. He complained to Devan Nair, then general secretary of the Singapore National Trade Union Congress, also very influential in the ICFTU regional organization, because the IUF regional office was at that time in Singapore and our regional secretary, Ma Wei Pin, was a Singapore citizen.

Devan Nair was to be elected president of Singapore in 1981, then was forced into exile to the United States and Canada in1985, having fallen into disgrace, a loyalist of an authoritarian regime betrayed and bitter. In 1981, however, he was still a militant defender of the conservative orthodoxy shared by the Singapore government and the ICFTU.

Newspaper articles started appearing in Singapore attacking the IUF. We had reason to fear for the safety of our regional secretary and for our ability to continue functioning as a regional office. This was a time when the Singapore government was cracking down on any opposition perceived as left-wing, Christian students were paraded on TV confessing to having endangered the security of the State.

We were not about to let our regional secretary become a TV star and we realized that we would not longer be able to operate freely from an office in Singapore, so we called on Ma Wei Pin to relocate to Geneva with his family (who at the time was fortunately in the Philippines on vacation) and we sent a secretary, who had never been in Singapore before, to close the office and arrange for the shipment of the archive and correspondence to Geneva. The IUF could no longer be repressed in Singapore because it had vanished.

Then the question arose: where would we locate to? We wanted a country with very stable and safe democratic institutions, as well as with easy communications for travel and internet. Two countries came to mind: Japan and Australia. We asked the Japanese unions who said “no thanks”, the Australian unions said “you are welcome”, so in January 1982 our regional office was moved to Sidney.

Ma Wei Pin, perhaps the only political refugee from Singapore, eventually became an Australian citizen and the IUF continued to defend trade union rights as it had always done.

What Bala had one was to help the IUF preserve its integrity in the face of threats from within the international trade union movement and to give an example of political courage with an important message both inside and outside the organization.

I visited Colombo several times in the 1980s and 1990s, and of course always the CMU building in Kollupitiya, and Bala and May. Her illness in 1995 and her death in 1998 were a very serious loss to Bala.

She had been very much his equal, a close comrade and companion, in life, in politics and in the union.

Bala had always been a basically tolerant person, not a wide spread quality in the Trotskyist movement, and toward the end of his life described himself no longer as a Trotskyist, or even a Marxist, but as a humanist. His main concern had become the survival of humanity, in the context of climate change.

Through the IUF Bala had discovered a dimension of the international trade union movement of which he had not previously been fully aware, the International Trade Secretariats, or international trade union federations by industry. the CMU eventually affiliated to eight (out of twelve at the time) and Bala won respect everywhere through his incisive and profound contributions at meetings of their governing bodies and congresses.

I should mention one more issue in the IUF where he played a leading role. In 1983 the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) of India, led by Ela Bhatt, had applied for affiliation to the IUF. SEWA was a split from the Textile Workers’ Union of India, by its Women’s Group which felt that their concerns were not adequately defended by the (male) leadership of the union.

SEWA, with a few hundred members at the time, was trying to achieve international recognition and support. In this, they were opposed by the entire Indian trade union movement, on absurd grounds: they were not really representing workers, they were an NGO and not a union, they were discriminating against men because they were an all-women organization. The IUF disregarded these objections and accepted SEWA into affiliation.

The controversy, however, continued at the regional level. The Indian unions attempted to keep SEWA marginalized. When it came to elect the Regional Committee, Bala defended the case of SEWA eloquently against the other Indian unions, and withdrew in the election in favour of Renana Jhabvala from SEWA, an unusual act of political generosity.

In the meantime, SEWA has close to two million members and its legitimacy is no longer challenged by anyone.

In 1997, when I was about to retire from the IUF, I and several comrades established the Global Labour Institute, a labour support organization, mostly in terms of consultation, networking, training and education. The GLI has an Advisory Board, and we were proud when Bala agreed to join this body.

Next to the original GLI in Geneva, Switzerland, another GLI was established in Manchester, and we have associated organizations in New York and Moscow. The GLI Manchester runs an international summer school every year in July on behalf of the entire GLI network. We had the pleasure and the honour to have Bala participating in the 2013 summer school.

Bala and I shared a platform to introduce a discussion on the “Political Challenge for the International Trade Union Organizations”. He was brilliant as usual. Later he worried that he had been talking too much about himself. He needn’t have worried: it was his story that captivated the audience. I introduced ourselves as totalling 173 years between the two of us. Not bad for a summer school principally intended for young people.

I think the 2013 GLI summer school was the last international meeting Bala attended. We will always honour his memory.

I thank you for your attention.