Coca-Cola has been bottled in Guatemala since 1939. The company does not directly own or manage the plants, but has franchise contracts with local bottlers. The main plant, with a monopoly of distribution to the capital city and surrounding areas, is Embotelladora Guatemalteca S.A. or EGSA. EGSA was originally owned not by Guatemalans, but by a rich North American family, the Flemings from Houston, Texas, who had made their money in oil.

After the 1954 military coup, the existing union at EGSA was crushed. Two years later, when her husband died, Mary Fleming brought in another Texan, John C. Trotter, as company President. Trotter, a fundamentalist Christian and fervent anti-communist, commuted regularly to Guatemala in his private aircraft, and from the first was directly involved in the day-to-day running of the plant.

In Guatemala, as elsewhere in Latin America, there are no national unions of the kind found in Britain, except among teachers and public employees. Instead, workers in industry have to organise separately within each factory and fight for legal registration for their union (personeria juridica), and then for recognition and bargaining rights from their employer (convenio).ln 1984 there were probably no more than 75 unions in the country, representing less than two per cent of workers. Apart from the risk of death, torture, and disappearance, workers have to face more sophisticated obstacles to forming and defending a union:

-

- Company- or government-sponsored unions or staff associations are set up whose members are paid higher wages than those in worker-initiated unions.

- Executive Council members must be literate, but many very able activists are illiterate

- Seasonal labourers on the plantations are not allowed to join trade unions, although they are often the worst paid and suffer appalling working conditions.

- Guatemalan labour laws favour small work-place unions, so secondary picketing is outlawed. Workers in the same sector, like teachers or banana plantation workers, cannot organise a joint action.

- Some trade union officials receive US-sponsored trade union courses which promote company loyalty and a commitment to company profits, and to working within the law irrespective of the nature of that law.

- Bureaucracy in the registration procedure often means delays of a year before a union is legally recognised.

Unions can call in inspectors from the Ministry of Labour and take employers to tribunals to press for recognition, bargaining rights and protection against dismissal. In practice however, there are only a few Labour inspectors, and they and the tribunals often cave in to pressure from employers or the military. ln the 1970s Labour inspectors and tribunal judges who stood firm were likely themselves to be threatened by the death squads.

Once a union is established, it may affiliate to one of a number of national federations, but these have little power and are seldom, if ever, recognised by employers. At national level, there is no single trade union centre, like the British TUC.

New attempts to organise

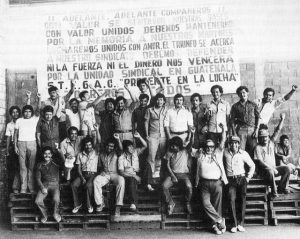

A new attempt to organise the Coca-Cola workers was made in 1968, but collapsed when one of the leaders, César Barillas, was kidnapped, tortured and killed. It was not until 1975 that the Coca-Cola workers again tried to form a union, at a time when trade union activity was increasing rapidly throughout Guatemala. The Coca-Cola workers themselves describe what happened the following year:

On 24 March 1976, at 2pm, a list was posted on the company notice-board, announcing the dismissal of over 160 workers, all of them members of the union. By 4pm the same day we had decided to occupy the plant peacefully and declare a strike. The occupation lasted for 16 days.

In their desperation to destroy the union, the managers decided to call in the peloton modela, the special patrol group, who arrived in two ‘Bluebird’ vans and various police buses and surrounded the plant, joining forces with the plant security guards. Shouting through a Megaphone, they ordered us to get off the premises immediately. Meanwhile, they were hunting for our leaders, to arrest them, but we barricaded ourselves into the garden on the street side. Then they waded into us, hitting out to right and left indiscriminately.

One group of workers was beaten really brutally, but instead of being taken to hospital, they were dragged off to secret detention centres. They didn’t reappear until some time later, when we found them at the Pavon prison farm.

The strike lasted until 8 April. It was a hard time for the Coca-Cola workers. We had to sleep in the street outside the plant, in all weathers, with only beans to eat, taking turns to mount guard. We had a tremendous amount of help from the CNT federation, as well as our valiant lawyers, Marta and Enrique Torres. Thanks to their efforts, on 8 April, 1976, we were woken up at 3am by fireworks and mariachi music. We had won, our union was registered, the 160 workers were reinstated and we all got back pay.

The going gets tough

The Coca-Cola workers had won legal registration of the union and reinstatement for the sacked workers. But this was only the first round in a much longer battle. They still had to obtain recognition and bargaining rights (convenio) from the company. Guatemalan workers have to face a whole variety of obstacles before securing full union rights (see box, headed Trade unions in Guatemala). Already Trotter, the company President, was employing a number of different tactics to break the union.

First, two hundred new workers were hired and offered better wages and perks on condition they did not join the union (although many did join later, when they realised how they were being used). Next, a staff association was set up under effective management control, and some of its members sent at company expense on ‘labour relations’ courses in Costa Rica. The association began to promote ‘family festivals’ and outings to the beach, all paid for by the company.

Trotter’s third tactic was to establish a dozen or more companies and divide up EGSA activity among them. In the labour tribunals, EGSA management argued that as the workforce was employed by separate companies, one union could not represent them. Marta and Enrique Torres, the lawyers for CNT and the Coke workers, responded by filing multiple wage claims for the workers in each of the new companies, and renaming the union STEGAC (Trade Union of Workers in the Guatemala Bottling and Associated Companies). Much of 1977 was spent in protracted proceedings with the Ministry of Labour and labour tribunals, with EGSA’s management continually inventing new pretexts for delaying recognition of the union.

The last and most important of Trotter’s methods of union-busting was physical violence and intimidation. In Guatemala, factory owners could hire members of the PMA, the Mobile Military Police, to act as armed guards in their plants. There was a fixed charge per guard per day, payable to the army. PMA guards were already used at EGSA, and more were now brought in. ln October 1976 Manuel Lapez Balam, one of the STEGAC leaders, was hospitalised for two weeks after one of the security guards drove a truck at him.

EGSA managers began to make explicit threats to Coke workers active in the union. On 10 February 1977 the personnel manager threatened Angel Villeda and Oscar Humberto Sarti. On 1 March, both were shot and wounded. The following day, the Coke workers’ lawyers, the Torres, were seriously injured when their car was deliberately bumped and forced off the road by a jeep driven by a government employee. Much worse was to come, and it was to affect not the only Coca-Cola workers, but the whole trade union movement in Guatemala.

The rising tide

The Guatemalan trade union movement had been decimated in the wake of the 1954 coup. Membership dropped from about 27 per cent of the working population, to less than 2 per cent. But by the early 1970s there were signs of a revival as a wave of strikes by teachers, bank workers and other unions shook the country.

On 24 March 1976, the day the first occupation at EGSA began, a new broad trade union grouping was formed, called CNUS (National Committee of Trade Union Unity). Sixty five unions of industrial, service and farm workers took part, including STEGAC and most of the other affiliates of the CNT federation. CNUS gave immediate support to the Coca-Cola workers. As the strikers picketed opposite the EGSA plant, delegations arrived from other unions — sugar and corn mill workers, power workers and workers from the INCASA coffee plant (which was owned by Coca-Cola), bringing donations in cash or kind. On 5 April CNUS threatened a general strike if the 154 EGSA workers were not reinstated.

The success of the occupation at Coca-Cola acted as a spur to other trade unionists, and throughout 1977 there were disputes in the banks, sugar mills and textile factories. Coke workers gave their support to all of these, and the brightly painted Coca-Cola delivery lorries became a familiar sight, arriving with refreshment for the pickets.

The event that really galvanised the trade union movement, and for the first time brought together peasants, industrial workers, students and the urban poor, was the march of the miners of Ixtahuacân in November 1977. Locked out by their employers when they tried to form a union, the miners decided to march the 160 miles to Guatemala City to put their case to the authorities. The march took nine days. Along the route, groups of peasants and other workers brought food and refreshment to the marchers.

One of them, Luis Castillo, described their arrival in the capital:

With our struggle, our weariness, our feet blistered and bleeding from the burning tarmac, we made our entrance into the capital. The people of the capital had never seen a march like this one before. Nor had we, come to that. You could see the emotion of so many people who knew we were setting an example for all. The bridges were thronged with people. Well-wishers would break through the lines to give us sodas, fruit juice and tortillas. We miners set an historic example that will never be erased from the minds of many compañeros.

One hundred thousand people turned out to see the miners’ march arrive. Marching with them were many of the Coca-Cola workers, and others from the unions affiliated to CNUS and the CNT.

On 29 May 1978 landowners and government troops massacred over 100 Indian peasants in the town of Panzas about 80 miles north-east of Guatemala City. CNUS and CUC, a recently-formed peasant federation, organised a joint protest demonstration in Guatemala City on 6 June which drew 60,000 people, including trade unionists, Indians, church groups and two bishops.

ln the capital, protest and repression were escalating rapidly. A city-wide strike by bus drivers in July left tens of thousands walking to work each day. When the government tried to double the fares, riots erupted with barricades, street fighting and buses burned, leaving 31 dead and 200 wounded by the police and over 1,000 arrests.

[pullquote]An avalanche of killings

1979

5 April Manuel Lapez Balam, general secretary of STEGAC, is killed by a group armed with knives and iron bars as he is delivering crates of Coca-Cola.

18 June Silverio Vâsquez, an EGSA worker, is shot and wounded by a plant security guard.

5 July An attempt is made to kidnap Marlon Mendizâbal, now the STEGAC general secretary.

October The 16-year-old daughter of STEGAC lawyer Yolanda Urizar is arrested, beaten, raped, tortured and temporarily blinded.

1980

15 February Armando Osorio Sanchez, an EGSA worker, is kidnapped in the EGSA plant and killed.

14 April Trotter sacks 28 workers and three union leaders. The workers stage a sit-in which is violently dispersed by the police with tear gas and machine-gun fire. When a labour inspector intervenes, he is pistol-whipped by an EGSA manager. The security guards refuse to allow the sacked workers into the plant, shooting and seriously wounding one of them.

1 May Two Coca-Cola workers are among 30 kidnapped and killed while on their way home after the tradition al May Day rally. The lips of one of them, Arnulfo Gomez Segura, are slashed with a razor, and his tongue eut out and placed in his shirt pocket.

14 May The leader of the management controlled staff association, Efrain Zamora, is killed, apparently after threatening to resign.

27 May STEGAC general secretary Marion Mendizabal is gunned to death at the bus stop opposite the plant.

20 June Lt Rodas, the personnel manager, is shot and killed by the guerrilla group FAR. STEGAC is blamed, and in reprisal STEGAC Executive member, Edgar René Aldana Pellecer, is shot and killed in the plant by Rodas’ bodyguards.

21 June Two STEGAC leaders are arrested in a massive police raid on the office of the CNT federation, and disappeared.

28 June Police machine-gun entrance to EGSA plant, wounding two workers.

1 July EGSA management call police to clear out strikers. 80 members of Special Patrol Group attack and beat workers. Marcelino Sanchez Chajón and another worker are kidnapped and disappear.[/pullquote]

The reign of the death squads

CACIF, the employers’ organisation, and the security forces fully understood the threat CNUS represented. CNUS’s founder, Mario Lopez Larrave, was assassinated in June 1977, and a number of other CNUS activists were killed in the first months of its existence. It was against this background that John Trotter stepped up this campaign against the Coca-Cola workers. In October 1978, STEGAC general secretary Israel Marquez narrowly escaped injury when his delivery lorry was raked by machine-gun tire. He had been ‘warned’ by two company managers. ln early December, Trotter warned that Pedro Quevedo, the STEGAC treasurer, would be killed unless he stopped his union activity. On 12 December Quevedo, one of the founders and a former general secretary of STEGAC, was shot dead while on his delivery round.

Trotter and other members of the EGSA management attended a series of meetings in November 1978 between businessmen and General Chupina, the new chief of police, to coordinate strategy against the unions. Shortly afterwards, the company hired three ex-army officers to fill the posts of chief of personnel, warehouse manager and head of security.

Lieutenant Francisco Rodas was the new chief of personnel at the Coca Cola plant. He was described by the union as “a former army lieutenant, dismissed from the service for drunkenness, an ex-commando instructor in the Panama Canal Zone, and an active member of the Secret Anti-Communist Army (ESA). When interviewing workers in his office, he did so with a revolver on the desk in front of him, and a bodyguard on either side.”

ESA was one of several death squads whose activities had rapidly increased since General Lucas Garcia became President of Guatemala in July 1978. A police spokesman told the press that ESA alone killed 3,252 “subversives” in the first ten months of 1979. The government systematically denied responsibility for such operations, laying the whole blame on “independent anti-communist death squads”. Amnesty International reached a different conclusion: “No evidence has been found to support government claims that ‘death squads’ exist that are independent of the regular security services. Routine assassinations and summary executions are part of a clearly defined programme of government in Guatemala.”

A common practice of ESA was to publish death lists. One ESA communiqué placed on the list, among others, Israel Marquez, the general secretary of STEGAC, and Frank LaRue, a lawyer for the CNT.

The Supreme Court of ESA has judged and condemned to death these cowardly, bad Guatemalans, who wish to seize control of our people and lead them into total communism. ESA has set a reasonable time limit. If, and only if, they leave Guatemala by that date and leave our people in peace, well and good. If not, sentence of death will be carried out.

NOW OR NEVER – the SUPREME COMMAND of ESA.

Throughout 1978, the Torres, STEGAC’s lawyers, also received repeated death squad threats, and reluctantly left the country for exile. On 2 January 1979, the entire executive committee of STEGAC received threatening letters from ESA at their homes. The only possible source of the addresses was company files. Then, on 14 January, general secretary Israel Marquez narrowly escaped an ambush by armed men at the entrance to the EGSA plant. For the next two days troops, police and men in plain clothes descended on the plant in unmarked vehicles, looking for him. He no longer dared return to his home, and slept at a different address each night. A couple staying at his house were shot and the husband killed.

Israel Marquez could no longer go to work, live at home or safely meet with friends or union colleagues. The only course left open to him was to leave the country, and he sought asylum in the Venezuelan Embassy. Before departing for Costa Rica on 29 February 1979, the STEGAC leader wrote a moving letter to his colleagues in the union:

I want to re-emphasise a point that you will remember has been constantly made: the union is not composed of a single person, nor even of an executive committee. Rather, THE UNION IS ALL OF US, AND EACH ONE OF US HAS RESPONSIBILITY FOR IT. The union does not exist because it is legally recognised, but rather because it represents the will of a group of workers who believe in one solid defence which includes all our workers; this is our union organisation.

ln considering the difficult moments which we are experiencing, the fury with which the company pursues me, and ail the crimes against each one of us, it is nevertheless clear that they will not succeed in destroying us; on the contrary, our union each day becomes better known to the working people of Guatemala.

After Márquez’s exile, attacks on the union multiplied. His successor as general secretary, Manuel Lapez Balam, was killed when a group armed with knives and iron bars attacked him while he was on a delivery round. A third general secretary, Marlon Mendizabal, was machine-gunned to death the following Year. In all, from April 1979 to July 1980, four workers were shot and wounded, four disappeared and seven killed (see sidebar below, headed An avalanche of killings).

When Israel Marquez left for Costa Rica he found the Torres and other exiles already there. Together they set to work to denounce the crimes being committed in their country. As they made contact with churches, human rights groups and trade unions in other countries, they began to establish a bew and powerful means of defence for the Coca-Cola workers and other trade unionists in Guatemala. Their work would act as a crucial form of support for STEGAC in what was to come.