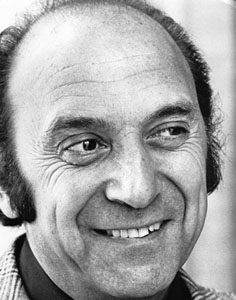

Funeral Speech for Charles Levinson, January 26, 1997, by Dan Gallin:

Friends,

We are here to honour the memory of Charles Levinson and I would like to say a few words on behalf of the International Federation of Chemical, Energy and Mine Workers and its General Secretary, Victor Thorpe. Vic Thorpe is now in Korea, and he will speak of Charles Levinson to a mass meeting of workers in Seoul today.

I would also like to speak on behalf of my organization, the IUF, of some of Levinson’s other friends and comrades in the international labour movement, and also on my own behalf.

We all know that we cannot capture the full complexity of a human being through his work, but we also know how important work is to the purpose of a life: to define the place of a human being in society and, ultimately, in history.

For most of his life, Charles Levinson was a trade unionist.

The essence of trade unionism is the fight for human dignity. Levinson was a leader in this fight, which he conducted with passion, with imagination, with joy and utterly without compromise on fundamentals.

He was a passionate fighter for justice.

In the international trade union movement he stands out as a builder of organizations and as the only important, original and creative thinker the movement has had in recent decades.

He moved into the area of international trade union work in 1951 as Assistant Director at the European Office in Paris of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the CIO, the more progressive of the two American trade union centers existing at that time. Between 1956 and 1964 he was Deputy General Secretary of the International Metalworkers’ Federation.

From 1964 to 1983 he was General Secretary of the International Chemical, Energy and General Workers’ Federation, which now has become the ICEM, after incorporating the mineworkers.

When he took over the organization, then called the International Factory Workers’ Federation, it was a virtually inactive body mired in bureaucratic inertia. He put life into it and transformed it into an effective and vibrant organization, today one of the most important international trade union organizations in the world.

In so doing, he defeated several attempts at putting parts of the international trade union movement under government control, in this instance the American government, and made a decisive contribution at that time to preserving the independence and the integrity of international trade unionism.

His achievement as a builder of organizations would have been impossible if he had not had at the same time a profound understanding of the forces in motion in the world economy, and a vision of how trade unionism must respond.

Today globalization is on everyone’s lips. He was the first to anticipate this development and to analyze its implications. He did so in three brilliant and seminal books:

Capital, Inflation and the Multinationals, in 1971, where he showed how the multinational companies, through their control of new technologies, were at the same time the spearheads and the chief beneficiaries of the incipient globalization;

In another book, published the following year, International Trade Unionism, he showed how the international labour movement must regroup to meet this challenge;

and in his book Vodka-Cola, published in 1979, he demonstrated the complicitous interaction between transnational corporate power and what was then the Soviet empire, and predicted what he called the “hybridization and consolidation of the worst features of both systems”.

In 1969 the ICF organized an international strike in Saint-Gobain. It was conducted simultaneously in four countries, with support from unions in six others, and it was the first internationally coordinated trade union action at the level of a large multinational corporation in the post-war period. It was also the practical demonstration of Levinson’s concept of international trade unionism. It showed the way forward for our movement.

In the labour movement, which is engaged in a permanent war for justice, one is defined by one’s friends and by one’s enemies.

Levinson made all the right enemies. He did not suffer fools gladly. He could be arrogant, and considering whom he had to deal with, he had every right to be.

Those of us who were his friends were deeply honoured by his friendship. His vision gave us inspiration, his defiant spirit and his irreverence for authority sustained our freedom, his wit and his humour gave us strength.

He loved life and laughter and he was a warm and wonderful human being. Everything he did came from the heart.

He was a good man.

Charles Levinson died on 22 January 22 1997 in Geneva at the age of 77 years. He was buried on 26 January at the Jewish Cemetery in Veyrier, Geneva.